The English Channel

I swam from England to France in 12 hours, 24 minutes

I felt strong the whole way

I was attacked by jellyfish

Fog shrouded France until we were within 1km of land

My crew were amazing

I’ve recovered really well

There’s still time to donate to my fundraising appeal

“All ashore”, “OK received”.

That is all that needed to be said between the boat pilot and the observer from the Channel Swimming Association at the end of my swim.

No fuss.

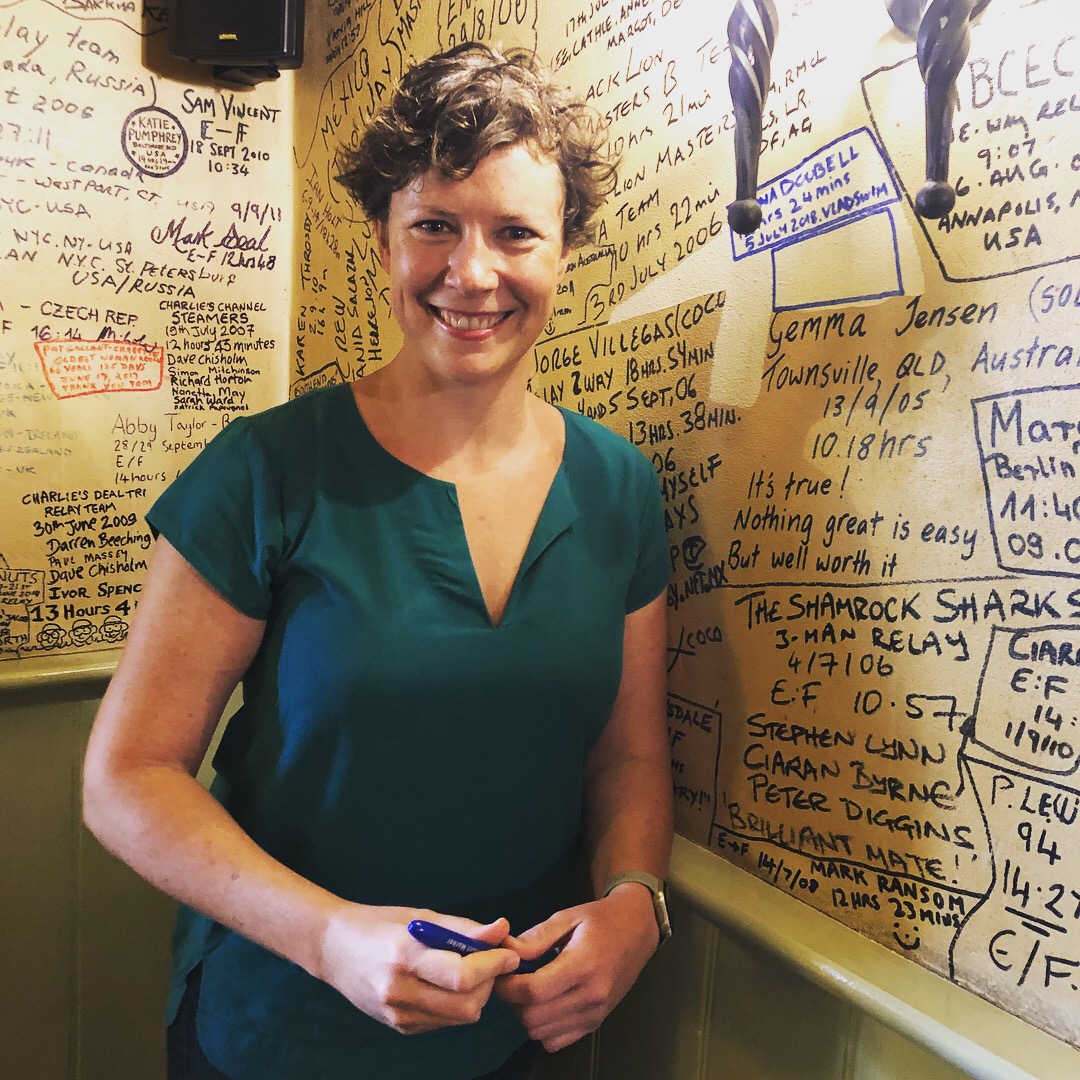

I completed my English Channel solo swim at 3:12 p.m. on Thursday, 5 July 2018, after two years of training.

Job done.

“Initial water conditions were glassy but with an underlying swell and slop from the last three days of significant winds. Overall, pretty good. ”

Swimming in the dark makes me nervous. I've only done a few night swims, and I haven't enjoyed any of them. I get confused by moving lights. I can't figure out how far away things are. And, well, it's swimming in the dark. What is there to like? But it is almost an inevitability with an English Channel crossing.

We arrived at Samphire Hoe just before 3 a.m. I had to ask the crew three times which way I was supposed to swim, because the small, misty moon gave almost no light. I jumped off the boat and blind trust got me the 20 metres from the boat to the beach. I heard the air horn blast and I started swimming.

The first two hours were awful. Never before have I had problems with troublesome thoughts in a swim. So the panic that engulfed me for the first hour was an unexpected, unwelcome surprise. I was overwhelmed by the enormity of the swim, I couldn’t think of any good reasons that I had taken it on, and I couldn’t find anything positive or constructive to think about. Eventually I came back to Vlad telling me to focus on my stroke. “Your stroke is the only thing that will get you there”. On repeat. I didn’t stop thinking of that until I reached France.

When it started getting light at 4 a.m I could appreciate the beauty of the glassy surface and the easy swimming conditions. But I struggled to find a comfortable position next to the boat: when I swam on the left side, I had the sun in my eyes, so I moved to the right, but that was a mistake – I got more fumes, and the boat was just a silhouette, leaving me unable to see the faces of my crew. So back to the left I went. I didn’t like faffing around so much, but I figured that I was going to be there for quite a while, so I might as well get it right.

I met my first jellyfish in the second hour. I have made it through eight months of training in Sydney without a proper sting, so even before I started the swim, I felt sure that they’d make an appearance. Mischee and I had agreed that I would yell out for antihistamine if I got stung and that she would pop one into my next feed; I could manage for half an hour without drugs. That all went smoothly. I only got a couple of light stings, nothing like the demons in Australia, so I knew I’d be fine.

But after a couple more hours, I ran into swarms of them. “Smacks” of jellyfish. Oh God, they were so thick! And they stung. They hit my face, arms, legs, underarms, everywhere. And they went on forever. I tried to focus on the positives: the water clarity was incredible (allowing me to see the jellies for metres and metres below me), and the diversity of the creatures was amazing – I’ve never seen so many species together. Quite a menagerie. And to give them due credit, there were some really beautiful ones in there. But there was no avoiding them. It was just a matter of putting my head down, knowing that I was going to get stung, and hoping that none of them got me too badly. I asked for painkillers, and hoped that my crew would keep an extra close eye on me, in case I had a bad reaction. I went through two ten minute patches in my fourth hour, and I jumped every time I saw one after that, scared that it might indicate another smack. Without doubt, this was the toughest part of the whole swim.

“Seven hours into the swim the sea became very sloppy and choppy with tide and wind creating a very disturbed sea. To add to the challenge, a very thick fog (visibility down to less than one cable) rolled in with the breeze. Stuart was concerned we may get to the French coast and not be able to land if the fog was too thick. This would not have gone over well with Anna. ”

After passing the smacks of jellyfish, everything improved. The rest of the swim, while not perfect, was solid. I wouldn't call it enjoyable, but I'm not sure it's supposed to be. If swimming the English Channel was fun, more than 1,850 people in the world would have done it!

I had two hours of great conditions when the rhythm of my stroke felt good (the only two hours that my technique felt good). That took me to six hours – what I hoped would be approximately half way.

I checked off eight hours – the longest swim I had done, and by that time, Mischee had told me that I was well positioned to reach Cap Gris Nez without having to double-back with the tide (meaning I’d be doing a 12-13 hour L-shaped swim, rather than a 14-16 hour S-shaped swim).

The only thing that played heavily on my mind was the fog. My nightmare was to emulate a couple of my friends, who had their swims cancelled 400 metres from French soil, due to low visibility.

For the last four hours of my swim, there were fog horns blasting, and massive ships appearing out of nowhere.I was oblivious to all this, but I could tell that visibility was not good. Despite the crew’s assertions and excitement that France was “just over there!”, I couldn’t believe that France existed. At all. It seemed just a hoax. “A conspiracy of cartographers”, to quote Tom Stoppard.

“At the ten hour mark, we asked Anna if she could lift her stroke rate to push through the slop into smoother coastal waters if need be. Her response amazed all on board; it was a very immediate ‘absolutely’”

Ten hours came and went, and I figured that this would be my last full round of feeds (four feeds, half an hour between each).

Just before the twelve hour mark, Mischee told me that this was my last feed and that the beach was just up ahead. I could see the hustle and bustle on the boat, as the tender was brought in and they got ready to accompany me to shore. I still couldn’t see land, but once again I proceeded with blind trust.

“Her final swim into the French beach was strong and incredibly, when she hit land, she actually stood up and ran up the beech to punch both fists in the air. Bloody amazing.”

And then the fog lifted. The beach was just a couple of hundred metres away. I swam until my fingers hit the sand. I stood up, waded through the waves, and ran up the beach, well clear of the water.

Job done.

Bemused French beach-goers congratulated me as I waited with anticipation for the air-horn to mark the end of my swim. It turns out that you don’t get one, so I unceremoniously headed back into the water to catch a ride back to the boat.

My face and arms were swollen from jellyfish stings. My throat was raw from the salt water. But I wasn’t cold. I wasn’t sore. I was all smiles.

I have been acutely aware of balance over the past week. I knew that I had trained enough to allow me to swim for hours, but I didn’t want to be cocky; I was super organised, but I had to dial back my control-freak tendencies, knowing that my plans could be scuttled by any number of surprises, and that ultimately, other people were in charge; the forecast conditions looked perfect, but my nightmare scenario (swim cancelled because of fog) felt like it was a possibility; I felt out-of-kilter for almost the whole swim, but my stroke rate barely deviated from 60 and my technique held through to France; the swim was physically demanding, but the head-space that the preparations commanded has been equally exhausting.

Now that it’s all over, I realise how much everything in my life revolved around the swim. I don’t (yet) feel directionless without a goal. At the moment it feels wonderful.

Thanks

For a solo sport, this game has involved a bigger support team than I had ever imagined.

My pilot, Stuart Gleeson, was brilliant. Communication with him and his partner, Karen, was always easy, and he’s just an all-round good guy.

Tony Lammi, my observer, was totally professional, friendly, took great photos, and seemed to genuinely enjoy the experience.

My boat crew – Mischee, Howard and Peter – well, I couldn’t ask for anything more. 100% committed, enthusiastic, practised, and seemingly thrilled to be involved. They did an awesome job with social media, feeding, encouragement and looking after me before, during and after. Five stars. Highly recommend. Would recruit again.

My “kitchen crew” (self-named) – Mum, Dad, Rose and Sue – kept me well fed, well slept, tolerated my nerves and waited on me hand and foot for ten days. Amazing.

Back at home, my coaches at Vladswim (Vlad, Martin and Jai) and at Flow (Richard) moulded my muscles, technique, and approach, and, along with my Vladswim family, somehow made the whole preparation fun.

Tara, my dietitian, worked with me to formulate the perfect feeding plan: at no point during the swim did I lack energy, feel sick, or (and I think this is the best indicator) feel mentally sluggish.

I have been overwhelmed by the messages of encouragement and congratulations from far and wide. It has been especially thrilling to hear how excited the kids get. Thank you all.

Fundraising to fight malaria

“You may well have saved a life – and have almost certainly saved people from a lot of suffering. Worth all the pain!”

When I got out of the water, I was really chuffed to see the number of people that had contributed to my fundraising effort while I was swimming.

Through my work I'm reminded of how much progress has been made in the fight against malaria, and yet hundreds of thousands of children still die each year because they don't have the simple and effective tools for prevention - like treated bed nets.

Nets cost only $2, so any donation - big or small - will make a life-saving difference to a child in sub-Saharan Africa.

So far, our efforts will provide protection from malaria for more than 3,000 families.

I know that with your help, we can save thousands more families from suffering.

If you’d like to make a donation, you can do so here.

Frequently asked questions

What worked well?

I was very lucky. It’s not possible to schedule an English Channel swim trip (holiday?) with any certainty – the conditions and your pilot determine which day you’ll swim (within the bounds of a week or so), so booking accommodation, day trips, flights etc is a bit of a nightmare, and you (and the people you’re travelling with) have to be prepared to be flexible. I swam on the third day of my swim window. This gave me enough time to settle into the house, carb load and get over jet-lag (I also had a few days in Switzerland for work, which really helped). The crew arrived in drips and drabs but we had enough time to meet Stuart a couple of times, see the boat, go over our plans and the back-up plans. I ended up being far more relaxed than I expected to be. We also had a fabulous house that slept ten people, with enough room for everyone to have their own space. My family did a couple of day trips, leaving me happily at home (the pessimist in me was scared I’d fall over and break my ankle if I left the house). After the swim I had plenty of time to rest and recover before leaving England.

I trusted my crew completely. There were times that I wanted to know how far it was to France, but I realised that asking would just take time, and knowing the answer wouldn’t change how I was swimming, so there wasn’t any point in asking. I knew that if I needed to sprint, they’d tell me. I knew that they were all competent, sensible people who worked well together as a team.

I set my alarm for 4 a.m. the day before the swim, so I was exhausted by early evening, and was able to get 5 hours sleep before getting up at midnight.

I sorted out out my feeds weeks ahead of my departure from Australia, which put my mind at ease.

Short feeds. I had planned to do three short feeds followed by a longer one to have a bit of a chat with the crew. But I didn’t really need to talk or ask questions or get motivated, so most of my feeds were quick.

I counted my feeds (or rather, I counted the two hour feed cycles), so I always knew how long I had been swimming for. I’m not sure that this would be a good approach for everyone, but it worked well for me.

What would you do differently?

Not much, really.

I would find something to focus on in the first hours of the swim, when it’s dark.

I’d take a look at the map so that I could understand what my crew meant when they said “You’ve hit the French shipping lane”, or “You’re in French inshore waters”.

I wrote motivational messages to myself on tape that were stuck to my drink bottle. I didn’t read any of them. So I wouldn’t bother with that.

I had two sips of champagne when I got home. That wasn’t a good idea. I almost fainted.

How do you eat?

Every half hour my crew threw me a drink bottle, attached to a rope. I flipped onto my back like an otter and drank.

Occasionally I had to take drugs. These were loose in a shaker bottle. I just threw those back before having my drink.

My first feed took 12 seconds. My longest took 31 seconds.

What did you eat?

Torq gel, Torq energy drink, Staminade and Milo (with water).

I averaged just less than 350ml of liquid and 50g of carbohydrates each hour.

I had no problems with my feeds. In fact, I can barely remember them. Usually the Milo sits poorly in my stomach but I can’t even remember a single Milo feed.

I can’t imagine trying to eat solid food while swimming. It would take too long and it would be way too hard to chew.

Do you wear goose / duck / sheep fat to keep you warm?

I wear lanolin (wool grease) mixed with zinc oxide, but it's for sun protection and lubrication rather than warmth.

What did you think about?

My stroke.

Excel.

That the last three letters of Sea Leopard are the same as Howard.

That my nose made a tooting sound when I breathed out.

Really profound things like that.

Why?

I don't have a good reason. It seems like a rite of passage once you've been with Vladswim for a while. And I really like swimming.

Also, this. It makes me laugh even more now.

How many people have swum the English Channel?

I am now one of around 1,850 people to have completed a solo swim across the English Channel. This includes around 580 women, 40 of whom are Australian.

Were your fingers and toes wrinkly afterwards?

No, I don’t think so. It certainly wasn't one of my top concerns.

Do swimmers get drug tested?

I've never heard of anyone being drug tested before, but yes, I was tested for drugs. Once I got off the boat in Dover, a CSA official took a saliva sample (with some difficulty) to test for recreational drugs.

How’s the recovery going?

Great. I had sore biceps and triceps for 36 hours but my body felt fine after that. No shoulder pain at all – during or after the swim.

The worst bit of long-distance swimming is how much your tongue and throat hurt after hours in the salt water – everything tastes awful. But mine recovered within two days.

The jellyfish welts faded within a week. I was on antihistamines for about four days.

I went for a swim nine days after the EC and I felt pretty good; a bit heavy for the first kilometre, but smooth after that.

I've slept well, been on excursions, and treated myself kindly.

What next?

I don’t know. No big plans for the moment.

Thanks for the suggestions, but I will not be swimming across the Bass Strait.

Key stats

Date: Thursday, 5 July

Start time: 2:48 a.m. UK time

Finish time: 3:12 p.m. UK time

Duration: 12 hours 24 minutes

Water temperature: 16c to 18c

Boat: Sea Leopard / Stuart Gleeson (CSA)

Crew: Mischee, Howard and Pete

Video

As I've said before, this isn't a spectator sport. But I've put together a playlist of videos so that you can see the conditions and critique my technique. Use the menu/hamburger button on the left.

Track

My amazing friend Kylie put this together:

Observer’s report

Tony Lanni’s report can be found here. It makes me tear up every time I read it.